The arrival of Europeans and tourists in Central Australia disrupted tens of thousands of years of Anangu history, but 150 years later, there’s a new appreciation for traditional wisdom

For anyone planning to visit Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park for the first time, there’s one thing you need to know about the experience of visiting this remote and beautiful part of Australia: Whether it’s staring in wonder at the night sky as you learn about the Anangu’s interpretation of the stars or waking at dawn to see Uluru emerge from the darkness, you will be profoundly moved by the power of the park’s history, people and landscapes.

Spiritual home

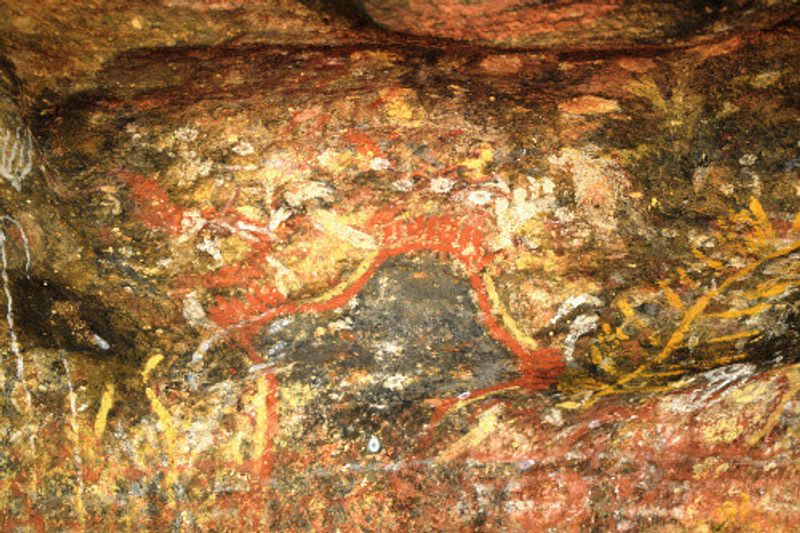

The stories of the Anangu, who are thought to have settled in this part of the Central Australian Desert between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago, describe how their spiritual ancestors created the animals, plants and rocks at the beginning of time, bringing the world into life as they moved across the land. Since that time, the Anangu have borne the responsibility of caring for the land and passing on the traditional knowledge of its wisdom, laws and customs (Tjukurpa) through millennia.

Guides are allowed to share some of this Tjukurpa, and as they describe to visitors the relationship of the landscape to the dreaming, rocks shapeshift into animals and spirits as the landscape becomes a world of stories.

While this is the way many visitors to the park will experience the Uluru-Kata Tjuta landscape today, in 1873 explorer William Gosse had a more prosaic outlook (although he was equally astonished by the view). When he first glimpsed Uluru, he described it simply as an “immense rock rising abruptly from the plain.” On a reconnoitre with his Afghan cameleer Kamran from their base camp at Kings Canyon, Gosse noted the sighting in his diary - the first on record by a European - then named it Ayers Rock after the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers, before returning to his primary expedition to find a route from Central Australia to Perth.

Millions of years in the making

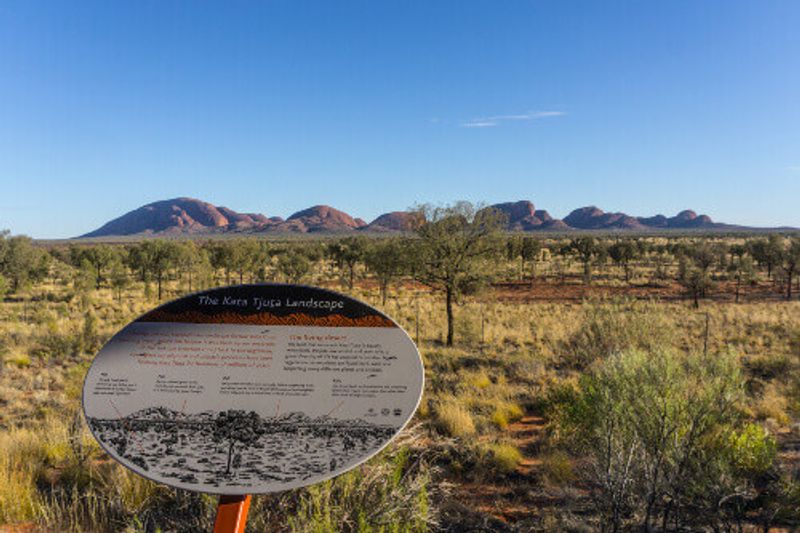

Despite speculation that Uluru and Kata Tjuta may have been the result of a massive meteor, the view that Gosse and Kamran were so astonished by is actually a rock formation that, along with its neighbour Kata Tjuta, had its beginnings around 550 million years ago, when erosion caused flat fans of sand and rock to form on the plains around the Petermann Ranges. These were later covered by the sea and the water pressure slowly turned them to solid rock. The sea eventually disappeared and movement in the tectonic plates caused the rocks to fold and tilt, creating the two distinct formations we know today. There’s more to both rocks that the eye can see: Uluru’s iconic red colour comes from the rusting of iron found within the grey arkose rock while Kata Tjuta’s texture, often described as looking like plum pudding, is a mix of granite and basalt and both formations are the relatively small tips of rock slabs that stretch another 6 km underground.

European arrival

Gosse was one of just a handful of explorers and surveyors who ventured into Central Australia in the late 19th century: Ernest Giles sighted Kata Tjuta (which he renamed The Olgas) a year before Gosse’s Uluru sighting, and a major surveying expedition was also carried out in 1894, establishing the area was unsuitable for farming and geological exploration. But apart from these journeys, few Europeans ventured into this remote and unforgiving territory.

By the 1920s a large area of South Australia and the Northern Territory, including Uluru-Kata Tjuta, had become an Aboriginal reserve - the name for areas of land allocated across Australia for Aboriginal people to live on - but this reserve area was eventually reduced so that the land could be surveyed for mineral exploration. As more Europeans began to travel to the area, a few small operators began offering guided tours.

Tourism and the Anangu

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the beginnings of tourism infrastructure were in place: in 1948 there was a road to Uluru and 1950 saw the declaration of the Ayers Rock National Park. Early tourists camped, but by 1958 there was an airstrip and permanent accommodation. People were fascinated by the landscape, Ayers Rock and The Olgas as they were commonly known, and the remote experience.

During this time, tensions with the Anangu, who continued to travel across their country as they had always done, continued until they were eventually legally removed from the land. It was the beginning of a long struggle to regain their right to their traditional country.

A return to the traditional custodians

It was almost two decades later after Indigenous Australians had achieved the right to vote and the broader understanding of Aboriginal rights and culture in Australia was starting to slowly shift, that the Aboriginal Lands Right Act of 1976 finally gave the Anangu an opportunity to reclaim their land. Despite many years of fierce opposition from tourism operators and the Northern Territory government, in 1985 the land was formally returned to the Anangu. Ten years later and 122 years after Gosse renamed the rock, the name Ayers Rock was officially changed back to Uluru.

Uluru-Kata Tjuta today

There were fears from some quarters that a change in ownership would mean the end of tourism at Uluru and Kata Tjuta, but the park continues to be managed jointly Parks Australia and the Anangu and the purchase of Ayers Rock Resort by the Indigenous Land Corporation in 2011 has seen renewed investment in the resort and its experiences.

Throughout its contemporary history, and from the start of its popularity as a tourist destination, Uluru and Kata Tjuta have inspired wonder and fascination, but in the early days of tourism, the Anangu were not central to the story of this extraordinary place. The past 25 years have seen that picture slowly change. Now their culture is central to the visitor experience, offering a perspective that brings the extraordinary stories of this unique natural wonder to the fore.