Explore the man-made geography of an ingenious piece of military history

A covert operation during wartime that has since become one of Vietnam’s largest tourist attractions, the Cu Chi Tunnels form a 120km portion of an even larger network that lies beneath Vietnam’s surface. Visitors have the opportunity to learn how Vietnam fought against military opposition that outnumbered and outgunned its own resources.

Beginning life in 1948, the Cu Chi Tunnels were originally dug in order to fight French forces during the First Indochina War, before the network was expanded to enable greater manoeuvrability and help soldiers avoid capture. The tunnels were expanded and refined again during the Vietnam War, becoming a base of operations for the Vietcong, as well an effective line of defence.

Tours of the site explain the ways in which this network was created and then maintained. An ambitious project, it involved adding larger rooms and antechambers. Parts of that network have been widened and reinforced to accommodate the large footfall the site receives each year, but it is still a tight fit in places: not least when trying to drop down the original, one-person manholes that formed some of the very first strategic points for soldiers to emerge and assault their combatants.

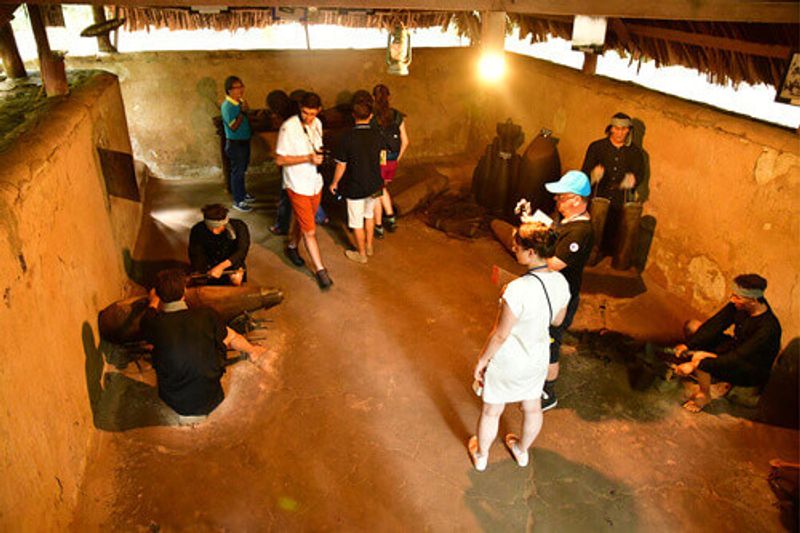

At its most narrow point, the section of the tunnels open to the public forms a 100m crawl likely to appeal to only the most adventurous of travellers. However, there are plenty of more accommodating spaces on display: rooms that served as hospitals, kitchens, living and storage areas each tell part of the story of how the Vietcong entrenched themselves.

In addition to exploring and explaining the site’s architecture, the tour guides of the Cu Chi Tunnels also talk visitors through the numerous military tactics used by the Vietcong to survive air raids and further disorientate opposition soldiers. These include various forms of camouflage and booby traps that utilise pins and spikes often made from bamboo that rise, fall or swing open to most commonly trap arms and legs – causing injuries that would not necessarily kill an assailant, but immobilise them and become infected. The overall effect was a theatre of war that intimidated the opposing forces, particularly when coupled dark, inhospitable terrain in which diseases such as malaria and wildlife such as snakes and scorpions were commonplace.

The Cu Chi Tunnels site also contains a firing range that provides a deafening sample of the environment that warfare created. Visitors can fire AK-47s and other weapons at a cost of VND50,000 (A$3) per bullet. A more sedate link to the past is the refreshments that replicate the simple but nutritious food eaten by the Vietnamese during wartime: dishes made from potato, cassava and peanut, along with tea. Souvenirs, in common with many the devices created to fight the Vietcong’s enemies, are fashioned from remnants from war, such as bullet casings and locally sourced materials. Together they form another part of the Cu Chi Tunnels’ inimitable legacy.